By Xenia Ferencevych

Dr. Paul Feffer always liked to make things. As a boy, his father, a professor of orthopedic surgery, brought home real mercury (you know, the toxic stuff), so that his son could make a barometer. Later, inspired by Carl Sagan’s television series, Cosmos, he took an interest in the skies, and picked up rocketry. While in high school, he had a summer job working for an architect creating a scale model of a hotel. And then, he taught himself to program computer software at the dawn of Apple and Microsoft when very few knew how to use a computer—and even fewer knew how to teach programming.

As a doctoral student studying at the University of California at Berkley, Dr. Feffer collaborated with scientists on three continents to build and launch a one-of-a-kind High Resolution Gamma-Ray and Hard X-Ray Spectrometer (HIREGS). Twice. (He calls it “an instrument” but most of us would call it “Wow!” More on this later.)

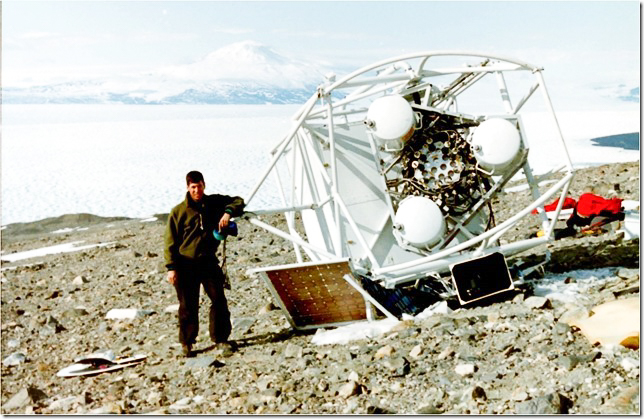

Dr. Feffer with HIREGS in Antarctica after its second flight

With the advent of The Storm King School’s new Q-terms last spring, Dr. Feffer proposed student projects such as making robots using resources like the School’s 3-D printer, creating a museum-quality scientific display and building an architectural model of the school’s campus.

Making things has helped Dr. Feffer understand the world—a curiosity that tends to lead people to the sciences. “I was always interested in physics and science, and astronomy and astrophysics,” he said. And while he’s always been keen on science, the path to teaching it and sharing it with young people has been a little less clear-cut.

ARRIVAL ON THE MOUNTAIN

Following 12 years of schooling on the West Coast where he received his B.S. in Physics from Stanford University and Ph.D. in Physics from the University of California, Berkeley, Dr. Feffer was restless. He’d been offered work in Pasadena, California at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, but doing “more of the same” held no interest for him.

Besides, he had aging parents back on the East Coast whom he wanted to attend to. They were both educators. His physician father taught at George Washington University, while his polyglot Yugoslavian mother “dabbled in teaching various languages.” After caring for them, maybe someday he’d head back.

Dr. Feffer had certainly felt the pull toward education during his early adult life—he’d been a teacher’s assistant in graduate school and also helped develop a weekend program teaching physics to at-risk junior high schoolers. And yet, his next move after California was not to the classroom. Instead, Dr. Feffer moved to the New York metro area and made the leap from academia to business.

Specifically, he pursued a combination of IT consulting and investment management in the banking and finance industry. His consulting company was called Positron Investments, Inc.—a nod to his study of positrons, “the anti-particle equivalent of an electron” in graduate school.

Later, he held the post of Chief Technology Officer at a small pharmaceutical distributor. Working with a team of computer programmers based in India, he developed the enterprise systems for managing customers, orders, vendors and inventory.

Somewhere along the line, however, that niggling interest in education cropped up again. He wanted to teach high school students.

“I saw it as a good thing to do,” said Dr. Feffer, “But the opportunity never really came up until several years ago when I decided, ‘Well, let me teach a college course’—I taught an engineering course at Rockland Community College—and I enjoyed that. That’s when I left my ‘industry’ job and started looking at schools in the area.”

Shortly thereafter, on the verge of entering an inner-city public school teachers program, he got a call from Headmaster Jonathan Lamb (Assistant Head at the time), inviting him to check out The Storm King School.

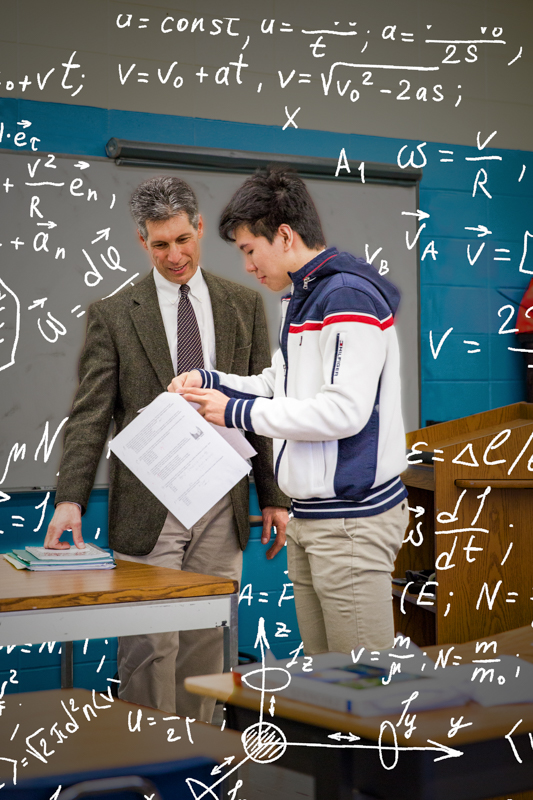

Dr. Feffer reaches out to a student in his Physics class

CHARLIE BROWN AND HIS FOOTBALL

For a high school physics teacher who never studied physics in high school (he chose biology instead, followed by physics in college), Dr. Feffer has quickly adapted. He also teaches computer science, manages the SKS Observatory and chairs the Science Department.

Though he commutes 45 minutes to work from Valley Cottage, N.Y., each day, Dr. Feffer stays late to coach the Tennis team and Outdoor Adventure, all part of the boarding school package. He doesn’t mind the long hours, and his weekend tennis game has improved.

But the pedagogical craft is not an easy one to hone. Dr. Feffer likens teaching to Charlie Brown kicking a football. That is, it’s like trying to kick a football that keeps getting pulled out from under him.

Since answering Headmaster Lamb’s invitation to come to the Mountain and join the faculty in 2013, Dr. Feffer has been “upping his game” one metaphorical kick at a time.

Not only has he had to figure out how to best teach physics on the high school level when not every student has yet been introduced to calculus, an essential building block of physics, but he’s also learning how to effectively reach our diverse student population.

The quiet authority with which he conducts his classes is also a powerful tool. When one observes him teaching, whether deconstructing the conservation of momentum or energy on the white board, or introducing rotational kinematics from handwritten notes, Dr. Feffer’s kind smile and relaxed style invite his students to engage with him.

With the project-centered curriculum becoming a standard at Storm King these last few years, Dr. Feffer is even more excited about his later-in-life career. The possibilities are many. His computer science students are making their own websites, programming Arduino circuit boards and learning about computer ethics (think Edward Snowden, WikiLeaks and the self-driving car). Big ideas, such as creating a preprogrammed miniaturized satellite called a “CubeSat” to send into space and monitor from the classroom, animate this normally reticent scientist.

Ultimately, it is the experiential assignments that fit best with Dr. Feffer’s own history as a Ph.D. candidate; a time when he studied X-ray and gamma-ray emissions from the sun, galactic center, and other astronomical objects using data collected with a balloon-borne spectrometer flown over Antarctica called HIREGS. The time when he helped to create and launch “an instrument.”

HARNESSING THE SUN

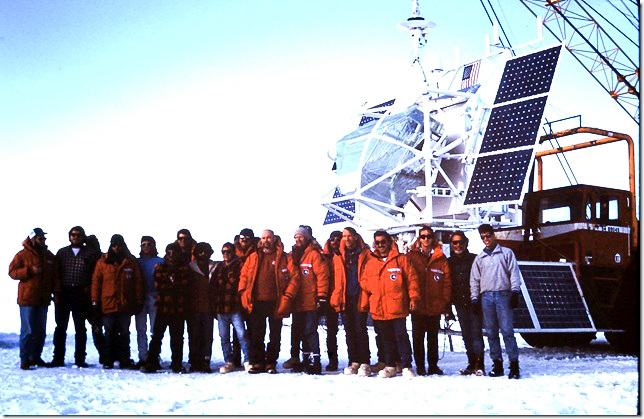

There exists a fascinating PowerPoint presentation that chronicles the fruition of Dr. Feffer’s graduate work on HIREGS. It shows photographs and video of him and his collaborators—scientists, and electrical and mechanical engineers—in Antarctica, assembling their spectrometer and sending it off on a long duration balloon flight (LDBF), getting it as close to the sun as possible. Studying the sun in Antarctica is ideal because it’s visible 24 hours per day during the summer season.

You can see military planes—presumably carrying the spectrometer’s various shields, detectors and computers created in labs in California and Toulouse, France—landing on a snowy runway at the McMurdo Station on Ross Island.

Dormitories, labs and dining facilities catering to military and scientific personnel fill the screen, as do images of Dr. Feffer’s colleagues inside in their workspaces, busily testing and putting together the parts in preparation for the launch.

Suddenly, spectacular satellite photos of the sun appear. Then comes the big day: shots of parka-clad folks joining the spectrometer with a parachute that’s connected to a gigantic, deflated high-altitude helium balloon, readying it for its LDBF. The mammoth balloon fills up with helium gas delivered from tanks, and rises until it becomes full size. It detaches and everyone cheers.

When asked what he felt at this very moment, Dr. Feffer replies with his characteristic earnestness: “I think at this point I was running back to the building. I wanted to see the launch, and I had my camera and I was taking pictures, but then I went back to start monitoring, making sure the instrument was working.”

The entire science and support team in Antarctica next to the HIREGS before its first launch

Yes, but this was the culmination of years of blood, sweat and tears; three months on a remote island, on an even more remote continent; what was he feeling?

“At this point, I’m worrying if there might be bugs in the software that I didn’t find,” Dr. Feffer laughs, referring to the computer program he developed to record their findings.

In January 1992, HIREGS circled Antarctica in 14 days, travelling about 5,000 miles. Then the crew repeated the experiment the following year. A summary of the findings is located at: sks.org/faculty/paul-feffer

Today, Dr. Feffer continues to make things. At home with his wife and young daughter, he is an avid home improver, enjoying, in his words, miscellaneous do-it-yourself projects.

Here on the Mountain, however, he is making scientists. By mentoring students in the classroom and on the tennis court, introducing them to the principles of science and technology, mixing in cutting-edge, hands-on projects and showing them the stars, he is filling our young men and women with the curiosity needed to better understand the world around them.

Dr. Feffer and Mr. Rowe observing their 2015 HVAL Champion Tennis team

For more information on the Science Program at The Storm King School, visit: https://sks.org/science